Old habits die hard, according to analyst Drewry, which in its latest Container Forecast report explained that rather than control capacity, the market’s instinct to preserve volumes and lower prices to secure short-term bookings kicked in.

Up until a few months ago, Drewry was fairly confident that container lines would take the necessary steps to reduce capacity before the market got completely out of hand. That confidence now seems to have been misplaced.

“We gave carriers too much credit by thinking they would proactively manage capacity. A deep-seated instinct to preserve volumes has kicked in, leaving carriers without control of the market,” said Drewry, noting that carrier behaviour was always a major risk to its forecasts.

“Over the course of this extraordinary phase in container shipping’s history we convinced ourselves – after much dialogue with various stakeholders – that a structural change had occurred in the industry, that consolidation and more efficient carrier alliances would help change old habits. That was wrong too,” the report continued.

“Belatedly, it is now clear to us that carriers have lost control of the container market, have failed to proactively manage capacity, and will act on capacity only when they are forced to do so by heavy losses.”

Failure to take action means that carriers are now “completely exposed to market forces”. The container bubble has burst and the record order frenzy of 2021-22 – which to date has seen some 6.7 million teu contracted – appears to be even more excessive than it did at the time.

While Drewry believes that capacity reductions will keep top line 2023 fleet growth relatively shallow at 1.9 percent, the easing of supply chain congestion will increase effective capacity at a much greater rate – a predicted 19 percent rise – returning the market to an over supplied position.

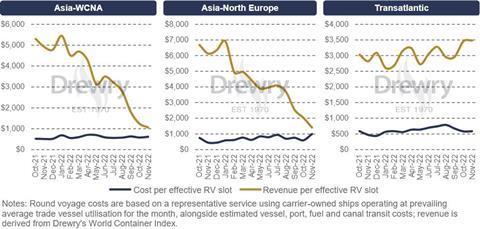

Drewry’s newest chart tracks the breakeven points for three East-West container trades (below). It described the chart as “a doomsday clock, counting down the time before carriers incur losses”. The closer the two lines are to one another, the more pressing the need to engage in capacity management.

“In our view, the fact that the chart lines are close to converging in Asia-WCNA and Asia-North Europe will drive further action, but it might remain at the edges of what is needed for a little while yet i.e. no immediate rush to lay up or scrap,” Drewry explained.

This is because carriers may want to hold on to see if there is a rush of bookings for the pre-Chinese New Year window (starting January 22, 2023). At the same time, the fact that the transatlantic remains a profitable playground provides an opportunity to cascade some ships there instead of giving up earnings potential by deactivating assets.

Given that loaded volumes are falling at an alarming rate and that rates are nearing breakeven levels, Drewry believes that carriers will finally get busier with some capacity cuts during 2023.

It added: “There will be no ‘managed decline’ (meaning very effective and timely matching of capacity with demand) as we described in the last edition. We still think there will be major capacity reconstruction, but it will be carried out to prevent freight rates from falling below breakeven, not to gently ease profit margins above historical averages.”